A three-part conversation with Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Stefan Vanthuyne

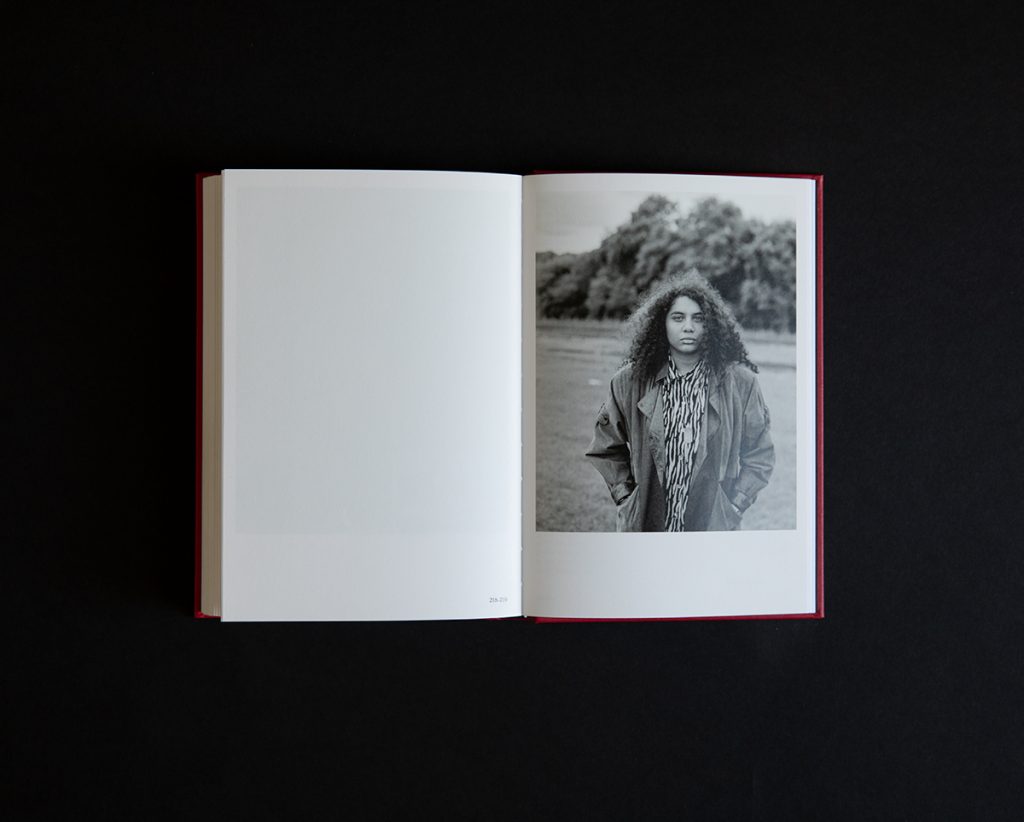

Spread from One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

In the closing interview in her impressive book The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2014), when asked by photographer Dawoud Bey how she hopes her work might function for the viewer, and how she intends her photographs to work on and for the viewer, given “that much of documentary has been predicated on an often disenfranchised or marginalized subject being visualized for a more privileged viewer”, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s response was as firm as the body of work that makes up the book:

This book is more than an art book or a book of photographs. It is a history book that lends itself to art history; the history of photography; American history; American studies; women, gender, and sexuality studies; comparative literature studies; health studies; social and economic studies; labor studies; race relation studies; and more. It is my testimony and fight for social justice.1

Audacious as this might sound, the work—which deals with the legacy of racism and economic decline in Braddock, Pennsylvania, and the impact it has on her family—does address all those topics in a way that is at once urgent, intelligent and heartbreaking. My own heart glows when I read her say this. However, the question remains as to whether Frazier’s book has in fact reached, or will reach the audiences or institutions that are interested in the topics she mentions, and what is necessary for it to do so, or whether it will mostly travel within an art-specific orbit. In the case of Frazier, I tend to worry not so much, as she is as much an artist and a documentary photographer as she is an activist.

Even if The Notion of Family, a very personal story that could not have been published in any other form than in a book, were to remain somewhat stuck in the art realm, she knows well enough when to pitch a photo essay to The New York Times when she feels a story of people who don’t have a voice needs to be told. In fact, few photographers today manage to find such a strong balance between documentary and art as Frazier does, all the while keeping in mind and staying true to what Martha Rosler wrote in 1979 about the critical issue of choosing or seeking an audience:

I feel that the art world does not suffice, and I try to make my work accessible to as many people outside the art audience as I can effectively reach. Cultural products can never bring about substantive changes in society, yet they are indispensable to any movement that is working to bring about such changes.2

Frazier is well acquainted with the writings of Rosler, as her interviews demonstrate, as she is with the writings of poet, playwright and theatre director Bertolt Brecht. His ideas on realism, and his conception of ‘epic theatre’ have been on my mind when it comes to the contemporary photobook, and to the question of how documentary photographers today use this medium as a way to tell complex and layered stories. I’ve been contemplating how contemporary practitioners of documentary photography use fiction and other visual strategies to build a narrative, and how their books become instruments through which they reflect on the current state of society, politics, media and visual culture.

Realism, Brecht wrote in 1958 in his essay The Popular and the Realistic, means:

laying bare society’s causal network / showing up the dominant viewpoint as the viewpoint of the dominators / writing from the standpoint of the class which has prepared the broadest solutions for the most pressing problems afflicting human society / emphasizing the dynamics of development / concrete and so as to encourage abstraction.3

60 years later, this thinking on the theatre seems very much alive and relevant. If we substitute Brecht’s focus on theatre with our focus on photography and the photobook, his arguments continue to resonate: “Methods wear out, stimuli fail. New problems loom up and demand new techniques. Reality alters; to represent it the means of representation must alter too.”4

When photographer and writer Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa visited Antwerp and the Photography Department of its Royal Academy of Fine Arts, I was eager to invite him for a conversation about these topics. He had not only contributed essays to monographs and catalogs by Vanessa Winship, Rosalind Fox Solomon and Paul Graham, he had also recently released One Wall A Web (Roma Publications, 2018), a book that brings together three different series of photographs—one consisting of old black and white press negatives collected on eBay—and creative and critical writing in order to reflect his own experiences of a United States torn apart by racial, economic and political contradictions. One Wall A Web won the Aperture First PhotoBook Award in November 2018.

Our conversation was a written one: I would share some thoughts and questions, mostly from a theoretical point of view, and Stanley would respond to them a few days later, going back to both theory and his own practice, his own book. Sometimes a week or more went by in between contributions. The whole thing spanned about three months. It is perhaps good to add that this introduction was written after the conversation. Here is how it began, somewhere near the end of April 2019:

Hancock St, 2014 (Our Present Invention) – One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

Stefan Vanthuyne (SV): I’ve recently been encountering, looking at and writing about photobooks where the written word plays an equally important role as the photographs in the narrative, and I’d like to start by asking you about your approach to text in One Wall a Web, knowing that the text in the book comes from different sources, and is as multi-layered as the images.

Perhaps I should add that while thinking about this conversation, I was also thinking about LaToya Ruby Frazier, whose work is more straightforward reportage or classic documentary and in general seems underrated in the art or photobook world; and in a perhaps less obvious way also about Moyra Davey, whose work deals with photography, writing and theory. A while ago I read her essay Notes on Photography & Accident, which includes all of the above, and I was slightly baffled at the shape it took, and by how loose, and almost nonchalantly associative the writing was. It felt somewhat ungraspable, as if it was trying to escape its own substantive meanings. I’m not sure how relevant this may be to our conversation, however, there was one quote from that text that really sticks in the back of my head: “I want to make some photographs, but I want them to take seed in words.”5

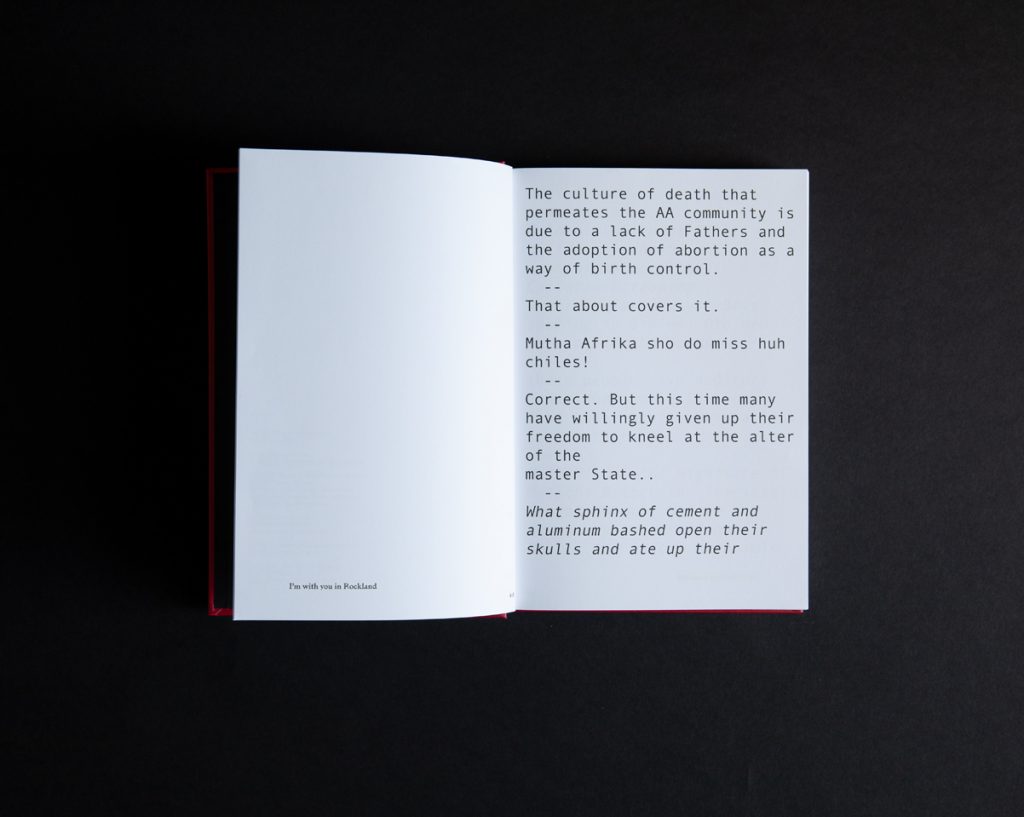

All of this being said, I was wondering about the opening text-collage in the book, I’m with you in Rockland, where you bring together parts of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and user comments you found on the far-right website breitbart.com. This text-piece was part of a work you did with American photographer Daniel Shea for True Photo Journal. Up until then I had known your writing mostly in the form of critical essays on photography. Had you done something like this artistic collage before, and what made you decide to take this approach in this particular case? And what did it do or mean for you in terms of text-image relations?

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa (SWW): I hadn’t done a piece of writing like that prior to doing this piece with Daniel, but it intuitively seemed like the most productive approach to his invitation to produce a verbal response to his series of photographs on the issue of white supremacy. I first tried air-dropping Ginsberg excerpts into the comment threads on breitbart.com, but couldn’t make them stick (they have hyper-vigilant moderators) so I decided to assemble fragments from each source in a kind of composite portrait.

I had seen the images Daniel had made already, but I made the text piece without looking at them directly or regularly. I think that both he and I wanted to produce a call and response, or create a piece of work in which our contributions intersected and interacted but weren’t intended to explain each other at all. Since we are both personally and artistically concerned with the various violences of political norms, and more specifically with the interactions of race and economy, I was confident that they would gel in some way, and then I was also not surprised to find that as a verbal piece, the text collage worked well as the entré into my book, as that took shape.

I would agree that that piece, and the other text pieces in the book deal with a world of images that’s rooted in words, to come back to Davey. In both the comments and the Ginsberg excerpts there’s a vividness and vitality to the image-world from which these violent, racist, misogynist delusions emerge and acquire such rhetorical and political force. I think that our use of words inevitably reflects the shape of the world we understand ourselves to occupy, or to desire, and recent changes in the tenor of public discourse (which affect our sense of physical inclusion within public space) can be tracked through language as a form of description, or imaging.

Spread from One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

The muteness of the photograph represents an opportunity for a certain kind of quiet, but nevertheless active contemplation, and I felt that it was possible in the interaction of word and image to freight the viewer’s/reader’s experience with some approximation of the complex demands placed on our attention in the contemporary moment. I think that that’s why comment threads were an important form to incorporate into the book. I also think that a palpable grammar that is expressly white masculinist and white supremacist undergirds the content of both text collages in the book, and that grammar has a powerful hold on a significant portion of the populace here in the United States, just as elsewhere in Europe, so the book as a form offered me an opportunity to summon that reality verbally, and potentially to encourage the viewer to respond to its possible relationships to the images as well.

I would add that while the possibility of working with text and image seemed like a way to explore their specific and singular strengths, it also afforded Roger Willems (the designer and publisher of the book) and I an opportunity to reckon with how one form (re)shapes the other: verbal discourses change how we move and look; visual images change how we think and read the world around us. In a way the book goes back to traditional documentary forms, in the conventional interaction of image and caption, except that in One Wall a Web they’re broken apart, and other texts intervene.

The interaction of word and image in the book hopefully collapses, or at least troubles the rigid distinction between the two forms: words image the world, just as our experience of the world as image constitutes a form of reading. If we think of the fraught issue of racial violence in the contemporary moment, and attempts to deploy visual and verbal evidence in cases of anti-Black violence like the murder of Eric Garner, it’s also clear that what words and images document still requires a form of reading. Judith Butler wrote powerfully about this in her 1993 essay Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia on the subject of the Rodney King video.

“The interaction of word and image in the book hopefully collapses, or at least troubles the rigid distinction between the two forms: words image the world, just as our experience of the world as image constitutes a form of reading” (Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa)

SV: The mention of Butler’s essay brings to mind Allan Sekula’s thoughts on photographic communication in On the Invention of Photographic Meaning:

The photograph is imagined to have a primitive core of meaning, devoid of all cultural determination. (…) In the real world no such separation is possible. Any meaningful encounter with a photograph must necessarily occur at the level of connotation. The power of this folklore of pure denotation is considerable. It elevates the photograph to the legal status of document and testimonial. It generates a mythic aura of neutrality around the image. But I have deliberately refused to separate the photograph from a notion of task. A photographic discourse is a system within which the culture harnesses photographs to a various representational tasks.6

In an interview with David Campany7, LaToya Ruby Frazier reflects on Gordon Parks’s The Making of An Argument, which deals with the 1948 Life magazine photo essay “Harlem Gang Leader”, of which NOMA curator Philip Lord writes: “In order to meet the expectations set up by the subtitle and the opening text, an overwhelming majority of the pictures selected underscore violence, fear, frustration, aggression, or despair.”8 Editorial choices, image editing and the altering of context changed the meaning of Parks’s photographs. Frazier says that if she was a journalist, she would not be able to edit or frame her photographs in such a way, and that instead she looks “for a narrative or context that will amplify the voices of the marginalized who have so many important stories to tell about America,” voices that are being kept quiet or written out of history “through whitewashing, cultural appropriation and media exploitation”.9 It seems to me that this is an important reason why documentary photographers today resort to the book as a medium for their photographic stories, as it generally provides them, as authors and communicators, with more control of the narrative.

SWW: I think the photobook is a paradoxically perfect and utterly imperfect site from which to work out the very arbitrary constructedness of social meanings (I’m thinking here of Sekula), and the dangers of an uncritical embrace of images. I say paradoxical because the form that gives photographers the greatest measure of creative freedom and precision is also a form that’s so expensive to produce, so difficult to support and publicise at the level of mainstream culture, thus so expensive to sell, and thus in such short supply as far as edition sizes go. I’ve been told on a few occasions that Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua book (Aperture, 1981) was released in an edition of 25,000 copies, which for a comparable novel would be modest but for a photobook now seems gigantic in scope.

The best-selling photobooks produced by the most well-known art photographers working today might reach half that size in two editions, and only if the first sells incredibly well, so just as column inches have shrunk along with the reach of print media, so too has the scope for the circulation of photobooks as well. I don’t want to suggest that somehow the photobook has improved in response to the shrinking space available in mass media; the 1980s were a decade in which seminal works like Chris Killip’s In Flagrante and Michael Schmidt’s Waffenruhe were published, and those books continue to represent peaks in achievement within the form.

Mark Neville’s photographic practice is one that takes very seriously the fact of meaning’s social, geographical and historical specificity, by addressing itself to and fashioning itself with and for the communities that the work addresses. Clearly LaToya’s book is also very relevant here. I think that Craigie Horsfield’s community-centered approach in the projects he has done in Barcelona and Utrecht (to name a couple) also does something substantive and layered, something that encompasses the local presence of the museum and the more dispersed address of the book in really powerful ways. Dana Lixenberg’s approach in her wide-ranging project Imperial Courts also represents an incisive and rich understanding of the ways in which an embrace of the specificity of community and geography can be profoundly generative, not just for art but for the people whom it depicts.

Armed Woman Shot by Police 1957 (All My Gone Life, Vol. 1) – One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

I’m interested in working out ways to be informed by all of that, although I should clarify that my work is not about single, specific, geographically or historically circumscribed communities. Its subject(s) is/(are) much more diffuse and disparate than that, as are its geographies. But I’m also cognisant of the fact that the sort of creative work I’m invested in producing is inseparable from the form of the photobook, and I should be frank about the extent to which I privilege that site over the sorts of curtailed spaces available for this sort of documentary work in other printed forms. One obvious conflict between the books and mass media platforms, as concerns work like mine, is that the scope of the work I make too far exceeds the available space within news or magazine media. I sometimes imagine if I were prompted to do something short-form that I’d end up, like W. Eugene Smith with his Pittsburgh commission, beavering away for well over a year, and winding up with 22,000 prints for an eight page feature.

(This was part one of the conversation, part two can be found here, part three can be found here)

__

1 Frazier, LaToya Ruby. The Notion of Family, Aperture, 2014.

2 Rosler, Martha. “For an Art against the Mythology of Everyday Life.” Decoys and Disruptions. Selected Writings, 1975–2001. The MIT Press, 2006, pp. 3-8.

3 Willet, John. Brecht on Theatre, Hill and Wang, 1964.

4 Willet, pp 110.

5 Davey, Moyra. “Notes on Photography & Accident.” Long Life Cool White: Photographs and Essays by Moyra Davey. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Accessed online at http://murrayguy.com/moyra-davey/texts/

6 Sekula, Allan. “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning.” Thinking Photography, ed. Victor Burgin, Macmillan Education Ltd, 1982, pp. 84-109.

7 Campany, David. So Present, So Invisible, Contrasto, 2018, pp. 60-67.

8 Fussell, Genevieve. “Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument.”, The New Yorker, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/gordon-parks-the-making-of-an-argument, last accessed on May 26th, 2019.

9 Campany, pp. 63.