A three-part conversation with Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Stefan Vanthuyne

One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

(This is part two of the conversation, part one can be found here)

SV: I’d like to address the question of how the photobook, as a cultural form rather than a work of art, can have an impact beyond the realm of museums and art institutions, later on. But first I want to follow up on what you were saying about how your work is inseparable from the form of the photobook. Besides being a space that allowed you and Roger to work with different image series and the text contributions, and to discover how they interact, it is also a space that, through the use of archival negatives in this case, allows for the past to be connected to the present—it’s a space that allows us to look back at that past and to confront it in terms of our current moment. In this way, photobooks deal with a longer period of time and with a certain way of looking at history. This, I think, is also something crucial that is not possible in traditional (news) media, as they are mostly concerned with the events of the day—events in fact that might accumulate over time to a history of sorts that eventually might find a place, in one form or another, in a book.

With this in mind, I was wondering if you could take us through the four year process that you and Roger went through in ‘assembling’ your book, some of the choices you made and perhaps point out some defining stages in that process. Could you talk about how you look at the period of time—or better: the idea or the concept of a period of time—that is now contained within the covers of the book, this period in your life but also in the social history of America, taking into account that during the time you worked on your photographic series (your own photographs and collecting the negatives) ideas must have been fluid and not fixed?

SWW: Jeff Wall has often said that he begins by “not photographing” when talking about his work, and in a funny way, working with Roger we began by ‘not making a book.’ I had an edit of the first sequence of photographs in the book (Our Present Invention) in autumn 2014, and Petra Stavast very generously insisted that Roger take a look at them while we were at dinner during Paris Photo, and he warmed to them immediately. I was, at that point, trying to make a physical maquette of the work, and Petra told him he should think about helping. We spoke the week after the fair, and he kept saying “if this were a Roma book, I would…” so at a certain point I asked him (very hesitantly and nervously) if he would be interested in publishing the work. When he said yes, I immediately said then let’s stop working on a maquette and think about making a book together instead.

We met up a few weeks later at his studio, during which time I’d shared a lot of the other work that wasn’t in the edit, and he gently but insistently kept pushing me to consider the broader spectrum of my creative practice, including the work I do as a critic or art writer, and to think about how we might make a book that gave an account of my various ways of being with photography beyond the narrow constraints of a well executed photographic sequence. He felt that the subject matter of the work, on the one hand, and then my various forms of engagement with photography demanded that we both reconsider the appropriate form for a book, and that we should take our time and slowly work out what that might be. I might have been leery of that sort of prompt from some publishers, but my familiarity with the incredible specificity of the books he makes, and of the way that they really give thickened dimension to the practices of the artists he publishes was more than enough to persuade me that this was a really good idea: to try to proceed as if we didn’t have the answer readily at hand.

So perhaps the first choice was that we wanted to make a book in which text and image would interact, and linked to that was an unspoken impulse to avoid the clean edges of a neat linear narrative with a clear beginning and end. By the time I’d spoken with Roger I was already some months into making what was then new work, All My Gone Life, so one decision I made was to dedicate myself to that new work fully, and to simultaneously start to try out differing forms of writing that might interact in some way with the images in Our Present Invention.

The Estates at Horsepen, 2014 (Our Present Invention) – One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

I tried writing narrative vignettes about encounters I had with people in the images. I tried writing more abstracted fictional narratives that were resonant with the setting of the work, but which didn’t describe a place or any of the people in the photographs. I tried writing prose poetry, and tinkered around with a sort of historical narrative that might contextualise the themes of the book in a more conventionally documentary form. I started to make some odd text collage pieces from differing texts: grand jury transcripts, conversations on 4chan (this was an early precursor for I’m With You in Rockland that I abandoned, but that has ended being foundational to the text collages in the book as it now stands).

Periodically we’d Skype, or I’d email Roger some images or a text, and we would generally stay in contact. Then we met up the following autumn in 2015 in New York, and I showed him an edit of the new and ongoing work in All My Gone Life, which I had still assumed would be something separate to the book we were working on, and he immediately said that that work needed to be part of the book. In my then quite rigid way, I’d assumed a ‘one-project-per-publication’ model, but it was clear when he suggested this that the two series not only could share the space of one book, but really needed to in some fashion.

It was as a direct result of Roger’s provocation that One Wall a Web, as something distinct from the two constituent projects, came into being as an idea, and that idea first materialised in an exhibition at the Kathleen O. Ellis Gallery at Light Work in Syracuse in 2016. The free interweaving of the two series, and as you’ve noted of the two substantively different types of images (my own, and the appropriated archival negatives) really animated the work as a whole, and from that premise Roger made a sketch for a design in 2017 while All My Gone Life was still in process, and we had the beginnings of the book we published in autumn 2018.

I think that the various kinds of interaction that take place between the texts (the two text collages, but also the Rukeyser poem, and the Ginsberg excerpt from America) and the images is fundamental to the work’s aims and successes, however limited those might be. And I think that, as you say, a certain amount of time and space is required for those interactions to be absorbed, and for them subsequently to change what one hears in the images and what one sees in the texts. A great deal of that interaction has to do with time as a conceptual and political phenomenon. The apparent antiquity of Rukeyser’s diction, or of the clothing in the appropriated archival negatives might suggest a certain historical distance, but that sense of distance is belied by the forceful clarity of the substance of the poetry, or of the appropriated images, which are intelligible to us now in expressly contemporary terms. In order for that sense of the presence of history in the present as a presence to be articulated clearly, we needed more space than a newspaper or magazine can afford.

In those sorts of formats, connections that are more elastic and volatile have to be quickly forced into productive order, and that’s a real problem for me, because one of the aims of the book is to explore the subtle and banal process of our incorporation into the violences of white heteronormativity, and to articulate how pleasurable and invisible that incorporation can be—to explore how ‘reasonable’ it can seem. That means the book needs to take certain risks with its viewer—risks that those mass media formats in most instances simply cannot afford. But I’m doing so in service of my belief in something that Susan Buck-Morss articulated some time ago, in a conversation with Grant Kester, where she was defending the forms of embodied knowing that aesthetic experience makes possible, because they “expose “reason” as power’s way of defending its own perpetuation.” She goes on to say that “[t]he problem is that a great deal of what passes for “aesthetic” experience veils material reality rather than opening it up for critical perception.”10 I felt that working with Roger through the form of the book might make it possible to unveil both the psychic and material realities of our moment and make them available for critical perception, and that the sensuous qualities of the word, of the image and of the printed book might contribute meaningfully to that effort.

I should add in closing that there was, I think not just for me but for many people—particularly minority groups—a palpable sense that the ground was shifting under our feet in the period in which I made the work (2012 – 2018), and in the period in which Roger and I made the book (2014 – 2018). Part of what drove that was precisely a sense of the recurrence of history, and of antiquated forms of racial and gendered violence, which serve to protect modernity as the privilege and preserve of whiteness. It was improbable that Barack Hussein Obama might follow George Walker Bush into office, just as it was (for a while, at least) that Donald John Trump might follow after. But a lot has surfaced in that interval, and the conditions of visibility, the politics of what can be made visible have certainly shifted in complex and important ways. History is deeply bound up in struggles over that changing politics, and I hope that my pictures are responsive to that.

Shirley Temple in “Dimples” 1936 (All My Gone Life, Vol. 1) – One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

SV: For some time now I’ve been looking into Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on the ‘epic theatre’ – it was Walter Benjamin’s essay The Author as Producer that led me there – and I can’t help but feel there are some significant parallels between Brecht’s ideas, and what is happening now with the contemporary photobook as an artistic medium responding to the politics of our times. Even if Brecht’s ideas on ‘epic theatre’ are nearly a hundred years old, I feel like both documentary photography, and the photobook today are in a somewhat similar state. The photobook and documentary photography are going through a lot of transformations, and are subject to a lot of experimentation in terms of not only the urgent and relevant stories they tell, but also in terms of questioning the medium of (documentary) photography in a more conceptual way.

Brecht used the term epic theatre for the first time when he referred to “the creation of a great epic and documentary theatre which will be suited to our period”.11

The essential point of the epic theatre is perhaps that it appeals less to the feelings than to the spectator’s reason. Instead of sharing an experience, the spectator must come to grips with things. At the same time it would be quite wrong to try and deny emotion to this kind of theatre. It would be much the same to deny emotion to modern science.12

Discussing the epic theatre of Brecht, Walter Benjamin writes that Brecht declared that epic theatre “must not develop actions, but represent conditions.”

These conditions are, in one form or another, the conditions of our life. Yet they are not brought close to the spectator; they are distanced from him. He recognises them as real—not as in the theatre of naturalism, with complacency, but with astonishment. Epic theatre does not reproduce conditions; rather, it discloses, it uncovers them. This uncovering of the conditions is effected by interrupting the dramatic processes (…).13

To do that Brecht looked at all the different elements that make up theatre—stage space, actors, music, plot, text…—in a way that one could argue is happening with the contemporary photobook right now, where artists are working and experimenting with (creative) text, form and design, where they are using fiction and other (visual) strategies, and borrowing techniques from other disciplines. Brecht was very much concerned with the changing of the medium—the ‘functional transformation’ of the medium, or the apparatus, as he referred to it—and in particular, he was concerned with its relationship to its audience, so that theatre could still be “reconciled with the modern world”, and that it could challenge the status-quo—both in terms of the old arts and society. This is something I think you’re addressing when you talk about the risks the book needed to take with its viewer as a way to unveil these realities of our moment.

Regarding aesthetics and what Buck-Morss says about it, I also wanted to share a letter to Fritz Sternberg from 1927, in which Brecht raised the question if (in theatre) we simply shouldn’t abolish aesthetics and instead adopt a sociological point of view. “The aesthetic point of view was ill-suited to the plays being written at present”, Brecht felt, and “their aesthetic vocabulary gave them very few convincing arguments for their favourable attitude, and no proper means of informing the public.” In the final lines of this letter, he mostly expressed a hope:

The works now being written are coming more and more to lead towards that great epic theatre which corresponds to the sociological situation; neither their content nor their form can be understood except by the minority that understands this. They are not going to satisfy the old aesthetics; they are going to destroy it.14

SWW: I wish I were that optimistic. Maybe on some days I am, but I think mostly I’m leery of grand sweeping movements, and of global scales of change. I suppose I have to be, to the extent that I’m invested in the photobook, because it’s such a niche object. As we write (in June 2019) I would guess that it’s incredibly unlikely that 500 people have sat and spent meaningful time with my book, and it would be incredibly unlikely were that number to have doubled a year from now. Maybe I’m wrong. But it’s hard for me to believe that I, and others also engaged in this field, are going to destroy the old aesthetics when you match up the audience numbers for the latest X Men movie with all the fine art photobook sales in any single year.15 I have no difficulty recognising that we live in a world whose governance is dictated by global flows of power and information, but I have great difficulty reconciling in my mind what a potential reader of my work in Micronesia might have in common with one in Marrakech, were I fortunate enough to have two readers in such places. I can only meaningfully think about the possible impacts of my work in a relatively local and small way.

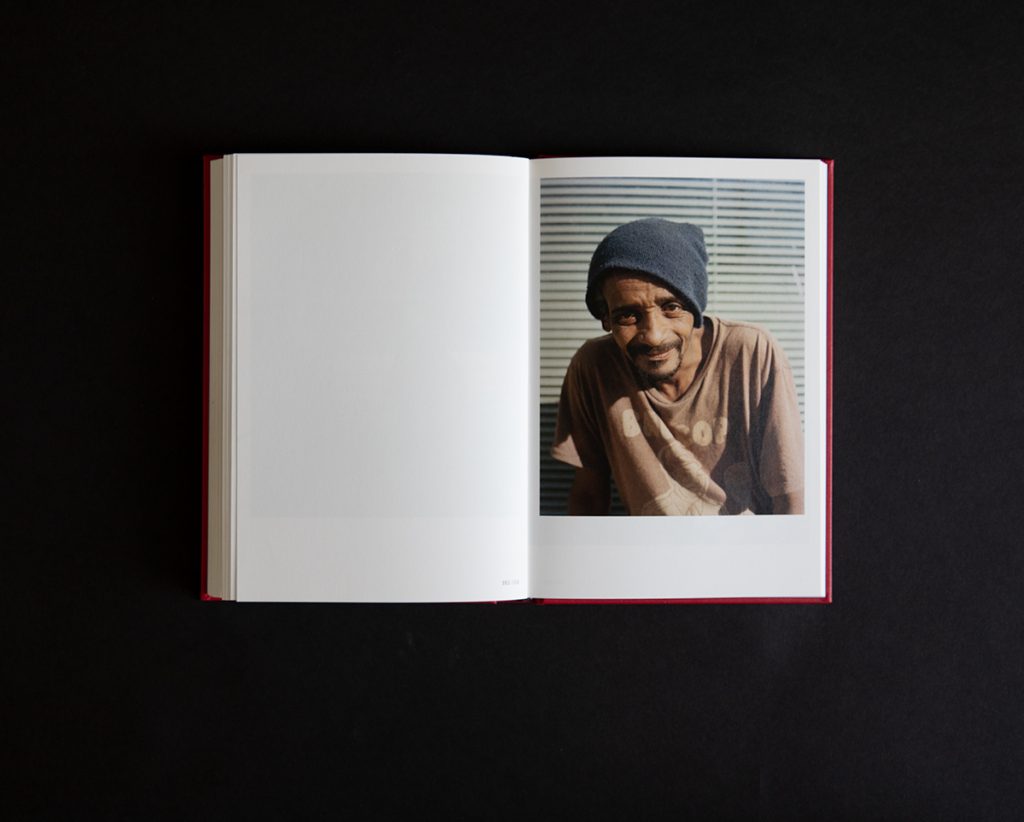

I had this wonderfully instructive experience at Offprint in London this year, in which a young white woman who seemed to be out on a Saturday with her partner approached Roger’s table in the Turbine Hall. There were hundreds and hundreds of people moving in and out of the building constantly, and she had found her way to our stand without much of any idea what these books were about, or who they were for. Roger told her that I was the author of the little red book she had in her hands, so she turned to me and asked me: “what’s your book about?” I replied, very predictably, “Why don’t you see for yourself?” I told her I was interested to see what she made of it on her own terms, so she started to thumb the pages quickly, and she landed on the opening image of the second sequence of photographs (All My Gone Life, Vol. 1) which depicts a woman wearing black heels and sheer black tights sat naked on a shitty sofa, screening the lower part of her face off from the camera with her upstretched left arm.

The visitor to the stall looked at the photograph, looked up at me, turned the page to see the following image of a dejected looking woman with a bra-top whose strap is falling off her shoulder, and who appears to be naked from the waist down, and she looked up at me again and said “Why did you make these pictures?” I told her that I didn’t, that I’d found them, and encouraged her to look around a bit either side of where she was, which she kindly did. She read a little of the end of the second text collage in the book, and saw a few of the images that followed that second dejected portrait, and more or less repeated her question: “Why did you choose to show this?”

The visitor looked at the photograph, looked up at me, turned the page to see the following image of a dejected looking woman with a bra-top whose strap is falling off her shoulder, and who appears to be naked from the waist down, and she looked up at me again and said “Why did you make these pictures?” (Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa)

I did my best to explain my interest, as an artist, in our ways of seeing the present, which she readily understood, but she couldn’t seem to understand why I would want to ask anyone to look at these images. Of course, the images she landed on, and that section of the book in particular are aggressively misogynistic, so the question bears repeating: why ask anyone to look at this? And I think the answer, and the substance of the lack of connection between she and I, devolve around whether you think looking (in the context of art or photography) can demand a certain risky ethical and reflexive labour, or whether it should guarantee an escape from that sort of labour. She didn’t particularly want to have to look at what the book showed, nor did she think it a good idea to invite other people to do so, and she was politely telling me as much. I think that she was suspicious of the extent to which I genuinely believed that what the book showed was in fact a problem. I think she was suspicious precisely because she associated the desire to look with the production of pleasure, which meant that I must derive pleasure from those images. I think that this only redoubled her rejection of the book, and her suspicion of me as its author.

The tricky part is that she’s obviously not wrong: I do enjoy the work that I make, and the opportunity to share it with others. I don’t think for a second that she had any difficulty understanding the ways in which those images of nude white women can immediately or instinctively solicit and reward misogynistic forms of desire and pleasure, nor do I think that I know more about the lived experience of that reality than she does. This is to say that I think she and I would agree that those photographs represent ‘real conditions,’ to come back to Brecht. The problem, or the basis of our disagreement lies in her rejection of the idea that such re-representation can redress or transform those conditions, and in her belief that the erotic charge of those images cannot be transubstantiated—cannot be made over into something else by the book itself. I suspect that for her the risk of failure in that effort far outweighs the possible benefits of success, and so the solution would be not to show the images at all.

I’ve come to realise that I think about looking at images differently, and that the archival plays a central role in this work I’ve made in meaningful ways precisely because of the fraught risk and potential that exists in the aftermath of one’s initial encounter with an image. Kaja Silverman talks about how ethics comes into play with our habits of looking not merely (or even principally) at the initiating moment, but through what she (and psychoanalytic theorists) call “deferred action”:

It may very well be…that there is nothing we can consciously do to prevent certain projections from occurring over and over again, in an almost mechanical manner, when we look at certain racially, sexually, and economically marked bodies. That does not, in and of itself, signify the failure of the ethical. The ethical becomes operative not at the moment when unconscious desires and phobias assume possession of our look, but in a subsequent moment, when we take stock of what we have just “seen” and attempt—with an inevitably limited self-knowledge—to look again, differently. Once again, then, the moment of conscious agency is written under the sign of Nachtraglichkeit, or deferred action.16

I tend to think that whatever new socio-cultural paradigm might emerge from this extended moment of violence and rupture that we’re differently but simultaneously living through will have to fashion itself from what is at hand, and moreover that it will have to reckon with its history so as not to repeat its iniquities. For me that means that I need to face up to my implication in those misogynistic images as a basic obligation of citizenship in some new, more ethically progressive polity. To the extent that those images produce pleasure through the symbolic and scopic supremacy that the camera affords the viewer, they can make that structural position (that supremacy) into a problem for the viewer. I might be pushing too far here, but I think maybe that that’s part of what the woman who visited the stall felt when she looked at them (a sense of that supremacy), and I think that she rejected that position, perhaps in meaningful part because she understood the cost of its seductions far better than I do. If I’m right about that, then in a way the work worked: the art object did its job, which was to incarnate real conditions, conditions of knowing that are inseparable from aesthetics and feeling, and conditions which in this instance resulted in her rejection of my book. That doesn’t hold out much hope for book sales, but it does preserve my faith in meaning.

Spread from One Wall a Web by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, published by ROMA Publications (2018)

But I’d also add that small local scale might be a help here for other reasons too, albeit the success of this art, and of these books, depends so perilously on people’s practices of reading and sharing, which we can only hope to motivate and reward with our efforts as makers. Pierre Nora wrote, in 1989, that “we have seen the tremendous dilation of our very mode of historical perception, which, with the help of the media, has substituted for a memory entwined in the intimacy of a collective heritage the ephemeral film of current events.”17 Part of the reason that I reject the notion in the Brecht you cite that we might, as artists, step outside of aesthetics into some neutral ‘sociological’ form is hopefully evident in the press photographs I’ve appropriated in my work: notionally neutral, and therefore supposedly un-ideological aesthetic forms are the optimal sites of ideological production. I’d argue, and I hope that the work demonstrates, that the “ephemeral film of current events” from which I’ve plucked a few frames, and which in its day was treated as a sort of sociological transparency, can be re-staged in such a way that that ideological work can be not only shown, but felt in its ongoing process of reproduction. We have to learn the relevant codes of visual culture in order to actively see this, and those codes are always local, and thus operative at local or regional but not global scales.

What I hope that my book—as an object in people’s lives—can do is contribute to the strengthening of practices of memory “entwined in the intimacy of a collective heritage”, as Nora describes it. I hope that some parts of the book speak directly to specific people, and can be made meaningful within their given contexts and geographies and histories on their terms, and that the images and words can be braided into local practices of memory, which begin precisely where we take up the opportunity to speak to another about who and where and what we are, and how we’ve come to be that way. That’s not about destroying the old aesthetics per se, on which a significant part of my photographic work actually depends, but about an attempt to catalyse local, individuated processes in which we might reconceive of our place in space and time, and in which we might revalue our relations to one another in recognition of the fraught and violently unequal ways in which we’re undeniably connected.

(This was part two of the conversation, part one can be found here, part three can be found here)

__

10 Grant Kester, “Aesthetics after the End of Art: An Interview with Susan Buck-Morss,” Art Journal, Vol. 56, No. 1: Aesthetics and the Body Politic (Spring 1997) p. 40.

11 Willet, pp 22.

12 Willet, pp 23.

13 Benjamin, Walter. “The Author as Producer.” Thinking Photography, ed. Victor Burgin, Macmillan Education Ltd, 1982, pp. 15-31.

14 Willet, pp 22.

15 I say X Men because it’s a shitty franchise, and not especially popular.

16 Kaja Silverman, “The Look,” The Threshold of the Visible World, New York: Routledge Books, 1996, pp. 173.

17 Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations, No. 26 Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory (Spring 1989), pp. 7-8.