Natasha Christia

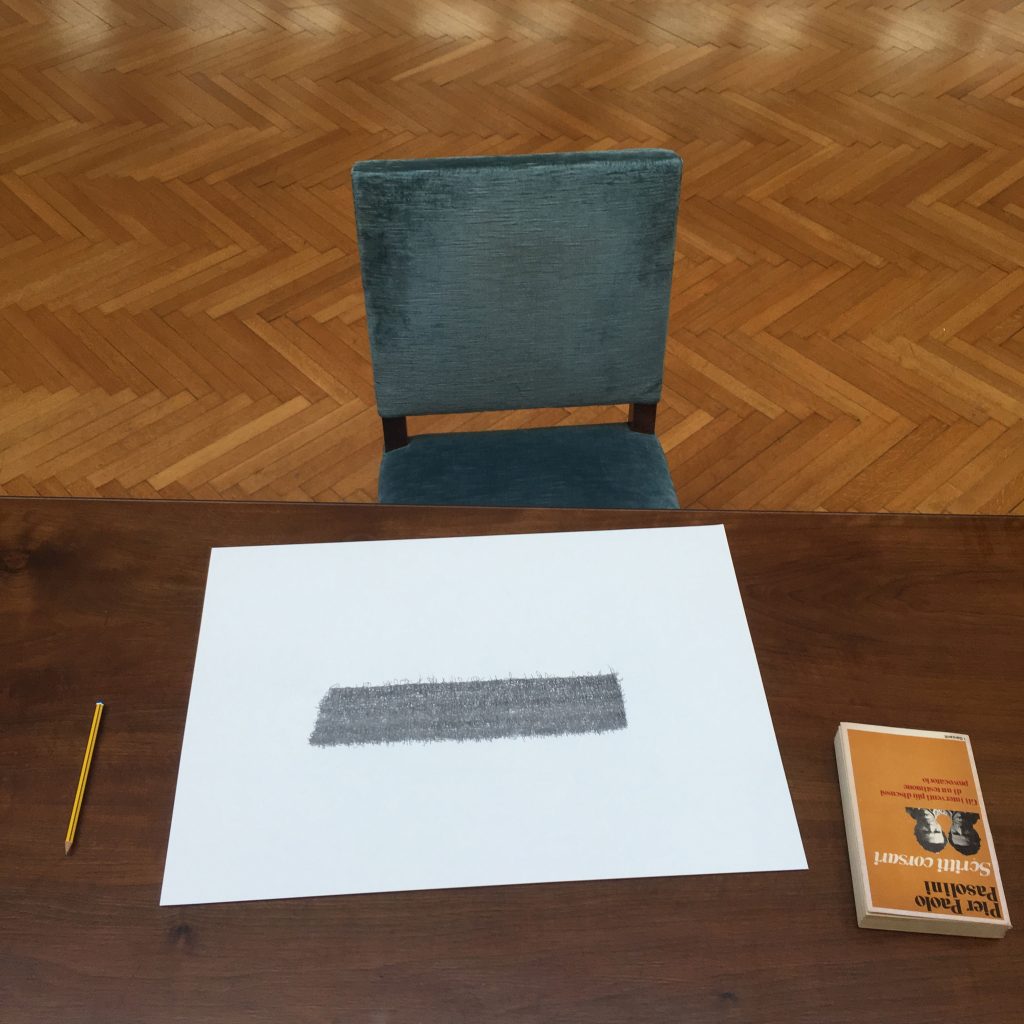

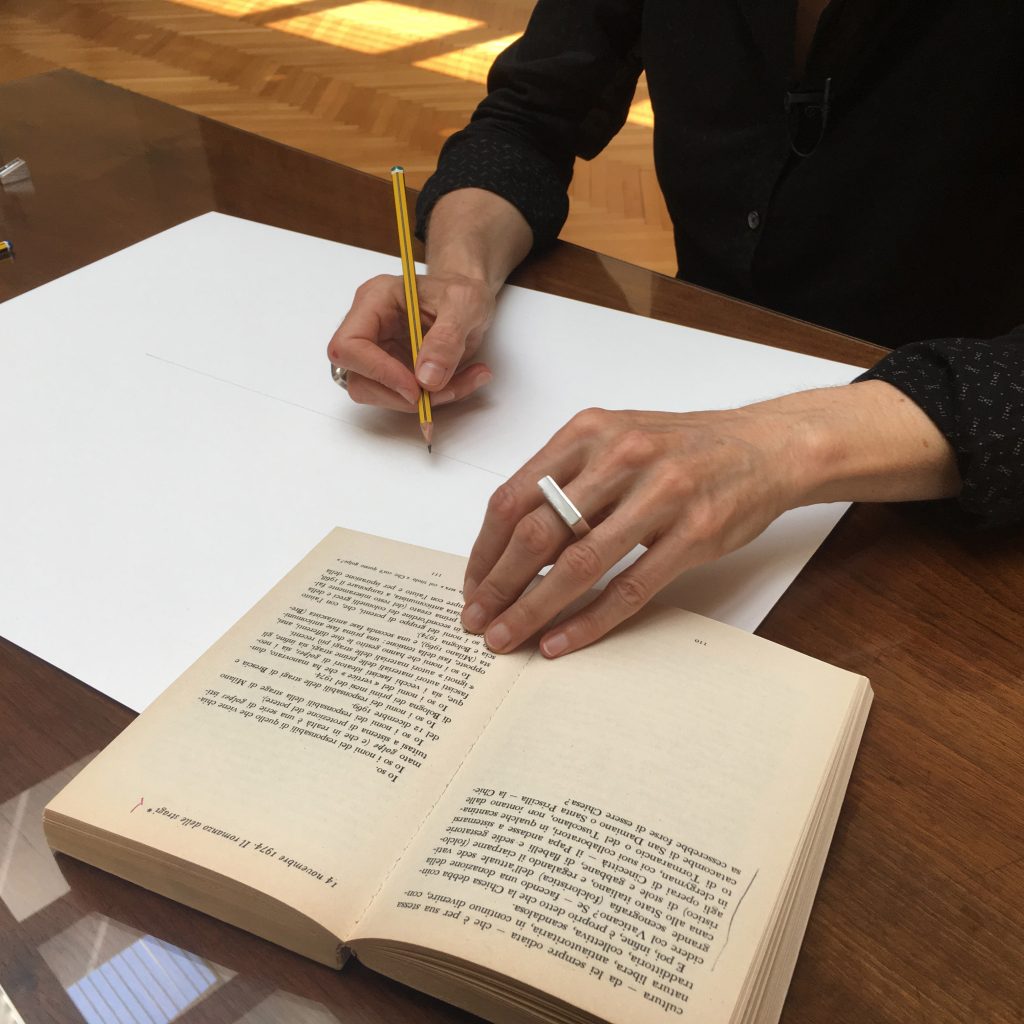

Chantal Vey, Omaggio al romanzo delle stragi di Pier Paolo Pasolini [Homage to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘The Novel of the Massacres’], writing performance and exhibition, Academia Belgica, Rome, April 25, 2019. Image ©: Chantal Vey.

My relation to books, not just (photo)books, provides the point of departure for this essay. Like everyone, in my case there has been a library, a bookshelf, the first reading of a forbidden book. A specific milieu of references has conditioned my approach. An accumulation of seemingly insignificant events has exerted decisive influence on my endeavours, experiences, and subjectivity. I am wholly indebted to each one of them for all the times they counteracted, jeopardised, broke my programmatic intentions into pieces, dismissing their blind execution. I could not agree more with Giorgio Agamben and his words about the resistance inherent in all creation, the “potentiality of not to do so”.1

I was originally invited to share here some thoughts on (photo)books and intervention. What follows is a series of ideas in the making, a theoretical morpheme that has manifested in my curatorial practice in a timid, often frustrated, and anecdotic form, and that only now begins to acquire sense.

I am not fully comfortable with the term ‘intervention’. It implies more than it can offer. You will therefore hear me repeatedly employ the term ‘potentiality’ in the following paragraphs, once again evoking Agamben. In a lecture I gave in Rome, back in March 2020, immediately before the global outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the word was latent; but now, as I am typing these lines, it resurfaces vehemently. Right at this moment, when no one can predict what the future will look like, the world as we know it asks to be reinvented, and in this unexpected event, potentiality is a dual key: not only does it presuppose a horizon, but it also acknowledges the actual possibility of envisioning it. The embrace of potentiality involves a position of awareness, accountability, and perspective that can ground and sustain individual and collective existence amidst our adverse times. Engaging in a conversation about our medium, the (photo)book, without taking these questions into consideration, seems futile and ethically in vain to me. We need to start ‘contaminating’ our debates and researches with what is happening in the outside world, even at the cost of succumbing to the winds of turbulent change out there, which cannot currently be controlled, directed, or even accurately described.

The embrace of potentiality involves a position of awareness, accountability, and perspective that can ground and sustain individual and collective existence amidst our adverse times

Within our small community there has been an acute misapprehension that (photo)book practice is solely about books. We are still overly concerned about the medium, its authority and crystallised outcome. And yet there is much more to how we produce books. It is about which books we choose to produce, what we are doing with them, and how through them we can relate with others in the world at large. Perhaps the time has arrived to address the potentialities of a distinct mental and sensorial experience of the (photo)book—other ways to engage with and share books and their contents—and to invite others to do so as well. Rather than formulating dogmas or ambitious programmatic intentions on impact, let’s experiment with alternative scenarios, subjectivities, and affective strategies. Let’s attempt to develop a relational philosophy around images and their dissemination systems (among them, books and exhibitions), and to put them into social practice, even at the cost of unlearning what we have learnt so far.

Oscillating between being a memoir of personal projects and an appropriation of philosophical and political-theory concepts, this essay will attempt to do just that. The goal of the quest is not ‘success’ but the humble and playful exploration of attitudes and situations, which can constitute useful operational tools over time.

The Toolbox

I have always been tempted by the profane. Perhaps this is due to my original background in archaeology. I recall that, as students, we were allowed to touch what other people were not. On repeated occasions, we became complicit with a questionable code of conduct by merely assuming that, when it came to their observation and display, historical and cultural artefacts should be treated as sacralised objects. We were relegated to the role of witnesses and actors in the ritualisation of an unassailable past.

I am reading Boris Groys in ‘The Museum as a Cradle of Revolution’ and as I do these memories occur afresh in my mind. According to Groys, “Objects placed in a museum […] are meta-objects, occupying a place outside of our world, in a space that Michel Foucault defined as heterotopic space”.2 I share this equation. But I would like to insert into it the (photo)book as well.

Groys takes his argument further when he refers to the ‘defunctionalisation’ of the language of these artefacts. “While these objects from the past—seen in the here and now—belong to the contemporary world, they also have no present use”.3 They perform their historical and cultural value as much as they allow us to observe and evaluate from afar relations that no longer exist in our society. I would add here that their distance/separateness from the here and now is a privilege and a curse. It either triggers critical reflection, or, inversely, freezes it through the banal illusion of proximity and safety that their context, i.e. the exhibition or museum space, provides.

I cannot think of any more ritualised and defunctionalised cultural artefact than the (photo)book. The invention of the term and its contribution in building within less than two decades such a long list of historical and contemporary authorities, milestones, and market values, designates it as a category apart that exists insofar as it is able to legitimise itself and its grand narratives. There are so many of these apparently harmless incisions of ideology, so many unquestioned practices of ritualisation and veneration, so little wonder about the stories we have not told and the books we have not produced. To this, one could add the fact that within the broad realm of fine-art photography, outside the academic circles of historiography, identity politics, and postcolonial studies, to interfere with or rework already produced bodies of work is often considered no less than sacrilegious.

I would like to keep the thread going on Groys with his citation of a passage from André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto (1924), in which Breton sees in miscommunication a hidden truth of all communication. As Groys comments, ‘Miscommunication here is understood as an operation of defunctionalisation of language and speech. Only if the other person defunctionalises conversation and information do we begin to accept them as sovereign and as thinking’. According to Breton, writes Groys, “Books are also confronted with these misunderstandings, especially by their best and brightest readers”.4 To which I would add: their makers, too.

Within the broad realm of fine-art photography, outside the academic circles of historiography, identity politics, and postcolonial studies, to interfere with or rework already produced bodies of work is often considered no less than sacrilegious

I propose incorporating these areas into our space for thought-provoking associations. It is this defunctionalisation—which is sometimes literally equivalent to fossilisation when it comes to addressing and exhibiting the (photo)book—that opens up unexpectedly ingenious situations of communication. For what is placed on the altar entails a critical distance, fostering an attitude of de-familiarisation that allows us to confront it anew. But are we ready for it? Are we ready to unveil and question the misinterpretations, misunderstandings, and fallacies inherent in our book projects, transcending our ideological comfort zone? Are we ready to dissect and scrutinise the eradicated modes of representation behind them, again and again, albeit without abnegating and cancelling them; without losing sight of the enduring present-day need to dynamically confront images and their systems?

I recall how, back in 2017, in Uncensored Books,5 one of my first book-based curatorial projects, we strove to address the potential impact of (photo)books as tools of activism against the flood of torrential world changes. Those were, admittedly, more optimistic times. I do not maintain the same level of ambition right now. The exhibition showcased book projects such as Lorenzo Tricoli’s (Other) Adventures of Pinocchio (Skinnerboox + d&books + blisterZine, 2016), Julián Barón’s Memorial (KWY Ediciones, 2017), and Edmund Clark’s Control Order House (Here Press, 2013). All of them were effective at manifesting, in terms of their content and dissemination processes, the ideological conflicts they conveyed. By performing their excesses, misuses, and ongoing polarisations, they themselves became meta-artworks of communication.

Nevertheless, it was Reversiones: Reversioned Books by Lewis Bush, Vincent Delbrouck, Brad Feuerhelm and Melinda Gibson6 that entered the profane territory of not just dismantling but also repurposing the musealised book object and its narratives within photographic history. The four (photo)book projects featured in this exhibition performed a critical re-reading of photography’s individual and collective historiographical milestones through the destabilisation of their own historiographical status, authorship, and hegemonic tales. In all of them, a purposeful de-familiarisation took place that interrogated and actively reformulated their original concerns and systems of representation in relation to their contemporary understandings.

Lewis Bush. War Primer in “Reversiones: Reversioned Books by Lewis Bush, Vincent Delbrouck, Brad Feuerhelm and Melinda Gibson”, E.Folio.001, Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City, 23 November, 2017–1 April, 2018. ©Installation shots: Mariela Sancari, E.Folio / Centro de la Imagen.

Here it is worth mentioning two cases.

The first is War Primer 3 by Lewis Bush, a reworking of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s War Primer 2 (self-published, 2011; Mack, 2018), which itself operates as a critical ‘redouble’ of Bertolt Brecht’s War Primer (German: Kriegsfibel, Eulenspiegel Verlag, 1955; English edition published by Libris, 1998), ‘updating and complicating its insights on image and conflict’.7 The stratigraphic display of the four editions on the wall, and the conception of the whole as an infinite, ever-expanding accumulation of a debris of interpretations, owed much to the notion of archaeological timescale as it explored the potential of the book to perform multiple critical tasks, while also revealing thriving disparities in interpretation and agency. As a whole, the installation could be seen as being aligned with the post-photographic credo that the overabundance of preexisting visual material in our hyper-documented world makes it unnecessary to produce new images (replace ‘images’ here with ‘(photo)books’). It was specifically concerned with the staging and performance of potential operations of re-signification and the communication of content, rather than with the actual content itself.

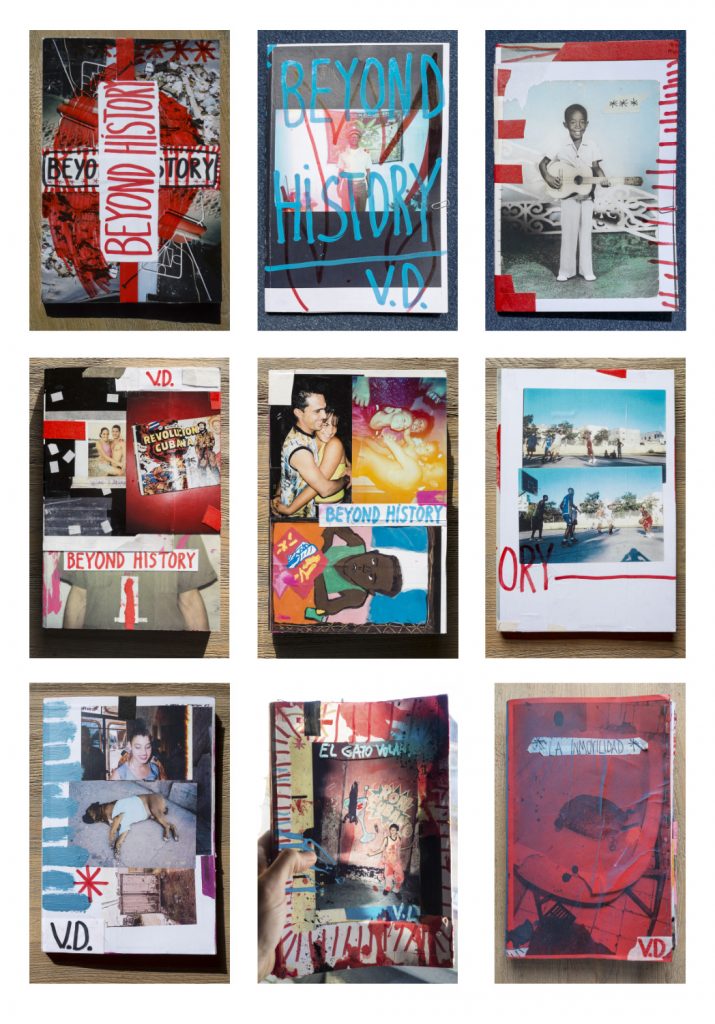

The second case, Vincent Delbrouck’s Beyond History, takes this meta-position to a frenetic extreme. Since 2014, Delbrouck has been revisiting his first book on Cuba, Beyond History: Havana 1998–2006, originally published by Bold Publishing, in 2008. By applying onto it alternative, handmade covers, and slipping small prints and photocopies between its pages, as well as supplementing it with original scrapbook material and drawings, he has created, to date, eighteen different versions. The eighteen variants of Beyond History are intentionally fractured and re-versioned, defying their proper authorial signature, format, and narrative argument. As Delbrouck explains, re-versioning the existing material, far from implying an intellectual or conceptual process, denoted the necessity to keep alive a specific body of work and period of his life by adding new elements connected to his present mood at a given time, and by openly contemplating and counteracting his practice as an artist.8 Delbrouck threw himself into the arena. He voluntarily betrayed his own tradition, dismissing its finitude, giving himself over to the process of remaking, and recorded his creative performances. Curiously, he is just one rare case in (photo)book practice; his plastic and visceral revisions are an exception.

‘Revisited Cuban book’ (originally published as Beyond History (Havana 1998-2006)) © Vincent Delbrouck

The very same questions about how to reanimate books and their concerns, and how to foster a disloyal reading, resurfaced some months ago. The perspective of crafting this essay led to ‘Deconstructing the (Photo)book and Reinventing it in Space’, a two-day experimental workshop, at Zoetrope in Athens, on exhibiting and developing in space (photo)book-based projects and (photo)books as objects.9 Workshop participants were asked to exchange their dummies or published photobooks, and to allow the others to interfere and interact with them in any way they pleased without restrictions. The quest was to test the actual possibility of intervention on (photo)books, embarking from the obvious plastic interventions and expanding to other fields including performance or even film. And then from there, by playing with the notion of failure and copying, to propel a novel creative and often subversive engagement with the readymade artwork, its content and authorship. As expected, that winter Sunday morning in Athens, the experiment was met with much resistance. The radical de-familiarisation from their ‘own’ object that took place in front of their eyes put participants in a vulnerable position, bringing to the fore the community’s aversion toward experimentation. Everybody expected an outcome until everyone realised that the outcome went beyond the production of visual artefacts. It was the very situation of resistance and its negotiation in public that mattered. That experience infused the experiment with ‘radical intimacy’—a term I borrow from Oliver Vodeb, and which I paraphrase affirmatively. That day, radical intimacy ‘created an autonomous space and occupied places meant for other kinds of relations’.10 The book turned into an interpersonal affair, giving birth to unpredictable collaborative and communicative situations.

On Potential History

Delbrouck’s Beyond History embodies this urgent quest to unlearn (personal and collective) history. In doing this, it turns unexpectedly from a playful aesthetic and poetic experience into an exercise of relational activism that defies, topples, and reconstructs anew the lexicon of artistic production and its authority commandments.

In this sense, the operations of potentiality it suggests echo remotely Ariella Aïsha Azoulay in her recent monograph Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism,11 wherein she addresses a series of attempts to “intervene in the imperial grammar of photographic archives, to interfere in imperial knowledge printed in books, to unlearn imperial structures […] and to foreground the imperial origins of numerous gestures inherited by scholars, artists, photographers and curators, and used in their practices”.

As Azoulay suggests, we have to invent new words, we have to relate in a new way with images to reconstruct possibilities that were erased by the sovereign power. We have to refuse attributes, change the power relations between them. As spectators we are participating in the event. Potential history is making the event for us. The first event is the mediation of the camera; the second, the mediation of the photograph.12 We have a third event here, too, created by another system: that of the book.

Beyond editing and publishing, our engagement with (photo)books can provide a space to rethink history and community ties, to perform their faults, and to create conditions for other possibilities and subjectivities to emerge. We have to dig into the past—or, alternatively, through dusty bookshelves. We have to go back to the constituent moment when the power and authority relation was created.

Once again, my background in archaeology tells me that there is a lot to be acknowledged. The unearthing of specific layers of the past and their selective preservation presupposes an act of violence: the effacing from the skin of the Earth of all stratigraphic layers deemed, in an arbitrary, authoritative way, irrelevant to the shaping of the communal narrative of the here and now. My background also tells me that beyond ‘cancel culture’, we should not erase layers, but should instead allow for a multi-directional and oppositional reading, even if it entails cacophony and an inherent, disorientating, and multi-chronological contradictoriness. With its chaotic process, its submission to the individual rule and non-programmatic mood, Delbrouck’s Beyond History embraces and catalyses this potentiality of being able to unlearn, write, and rewrite as much as it takes.

What follows is a list of the operational tools Azoulay proposes: Rejecting; Refusing; Historicising; Transforming; Creating; Reconstructing; Shaping; Using; Restoring, Imagining, and Inventing; Extracting.13 These tools can be adapted within any image system (books or exhibitions). Their use is not compulsory, nor are they exclusively associated with historical publications; indeed, they can prove useful when engaging creatively with contemporary (photo)books. It also seems to me that the toolbox has been there for decades—untouched. I do not fully grasp why.

Susan Meiselas. ‘Mediations’ (curated by Carles Guerra – Pia Viewing). Antoni Tàpies Foundation, Barcelona. October 11, 2017 – January 14, 2018.

Back in the mid-nineties, Susan Meiselas incorporated, in Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History,14 self-reflective and collaborative practices alongside the use of archives and ethnographic techniques. Her project evolved from documenting the evidence of the genocidal slaughter and exile of the Kurdish people to gathering a visual history that portrayed their desire for a homeland.

These are some of the pertinent questions she posed: ‘Every picture tells a story and has another story behind it: Who’s photographed? Who made it? Who found it? How did it survive? I wonder what we can know of any particular encounter by looking at such a picture today. We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making’.15

It would be instructive to implement into our own photobook practices Meiselas’ quest to return the objects to their narratives. Similarly we could wonder how their protagonists, makers, and readers cross one another’s paths, and what this interplay of agencies can bring about. In the decades following its publication, Kurdistan derived as various multimedia installations. Their most living iteration has been (photo)book-based workshops with the Kurdish diaspora that continue to be held wherever Meiselas’ Kurdistan exhibition is shown. The outcome of these workshops are zines of personal memories that add up to an archive of documents, images, and memories, thereby involving and giving voice to individuals and communities that have been subjected to violence and oppression.

I suspect that Meiselas’ practice, employing as it does the (photo)book not just as an artefact, but rather as an encounter and an event, could serve as a means for restoring a more affective sense of community that is missing from how we experience books, and from the way we relate to images in general.

To begin with, it implies a shift in vocabulary. Start by substituting the word ‘event’ in place of ‘object’: the book as a physical event, the book as an event of exchange, the book as an event of refusal, as an event of new narratives, as a reinvented/repurposed event.

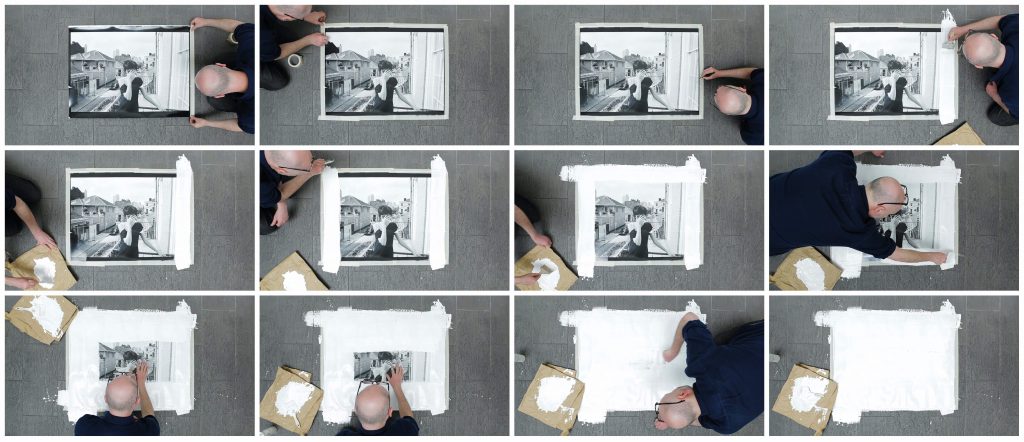

In this category of thought belongs Alex & Me by James Pfaff,16 a (photo)book I had the opportunity to review some years ago. Formulated as an ‘artistic reappropriation of an archive, a tribute to a significant broken love, [and] an authentic road trip through North America in the late summer of 1998’, Alex & Me is an intimate, diaristic memoir, with late-millennial nuances maximally explored through different forms and media. The publication served as a point of departure for various situations that the artist, alongside curator Francesca Seravalle, developed, between 2016 and 2018, in order to document the evolution of the project and the responses of his co-protagonist, Alex, to it. There was Alex & Me – Exhibition/SLP, a retrospective touching on the role of obsession in artistic research, for which the author made use of his archive and ephemera to ‘help rebuild fractured memories’; Alex & Me – One Day?, a single-channel video work of the artist literally intervening with a print from the series; Alex & Me – Coda, a mixed-media work, realised as an installation and as an artist’s edition; and Alex & Me – Outside, a large, experimental, mixed-media wall composition with photographs, made when Pfaff’s contact with Alex was severed for good.17 Just like Meiselas, Pfaff divided his role between maker, collector, writer, reader, performer, and agitator.

James Pfaff. ‘Alex & Me – One Day?’ A performance/single channel video work in loop, spoken word, HD 6:16, 2018. Realised as a video installation and presented at NIDA, International Photography Symposium, Nida, Lithuania, 2018, The Nuit de l’Instant 2018, Les Ateliers de l’Image/Centre Photographique Marseille, Printemps de l’Art Contemporain, Marseille, France, 2018 and in Edinburgh, Scotland at the Society of Scottish Artists, Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 2018—2019. The work forms part of Street Level Photoworks video programme.

The Field of Emotion: An Afterword

Which brings me to the afterword, and core, of this essay. For me, the (photo)book seen as an encounter and event is inextricably associated with the ‘field of emotion’, a concept addressed by Kader Attia in his eponymous essay exploring the legacy of colonialism.

“The work of art […] is always discussed, even hated, but never meaningless”, argues Attia. “Why? Because it incarnates the field of emotion! It is both a projection and a necessary mirror of society that seeks to exorcise its evil in order to find inner peace […] and thus to restore peace in the community”.18

Aristotle called that ‘catharsis’. Attia calls it the ‘field of emotion’.

What becomes obvious is that conceiving the (photo)book as an encounter and an event automatically raises demands on us and on what we can do with it. We are in need of generating more creative ‘situations’ when it comes to engaging with books. Situations that re-orchestrate the moment of writing and reading, and allow for more inclusive environments of hospitality, discussion, and knowledge production touching upon all categories of society.

Attia defends the urge to recover the field of emotion in public debate with the aim of healing—while still keeping the traces of the wounds of history visible. But healing implies repair, and that we relate with images in a new way.

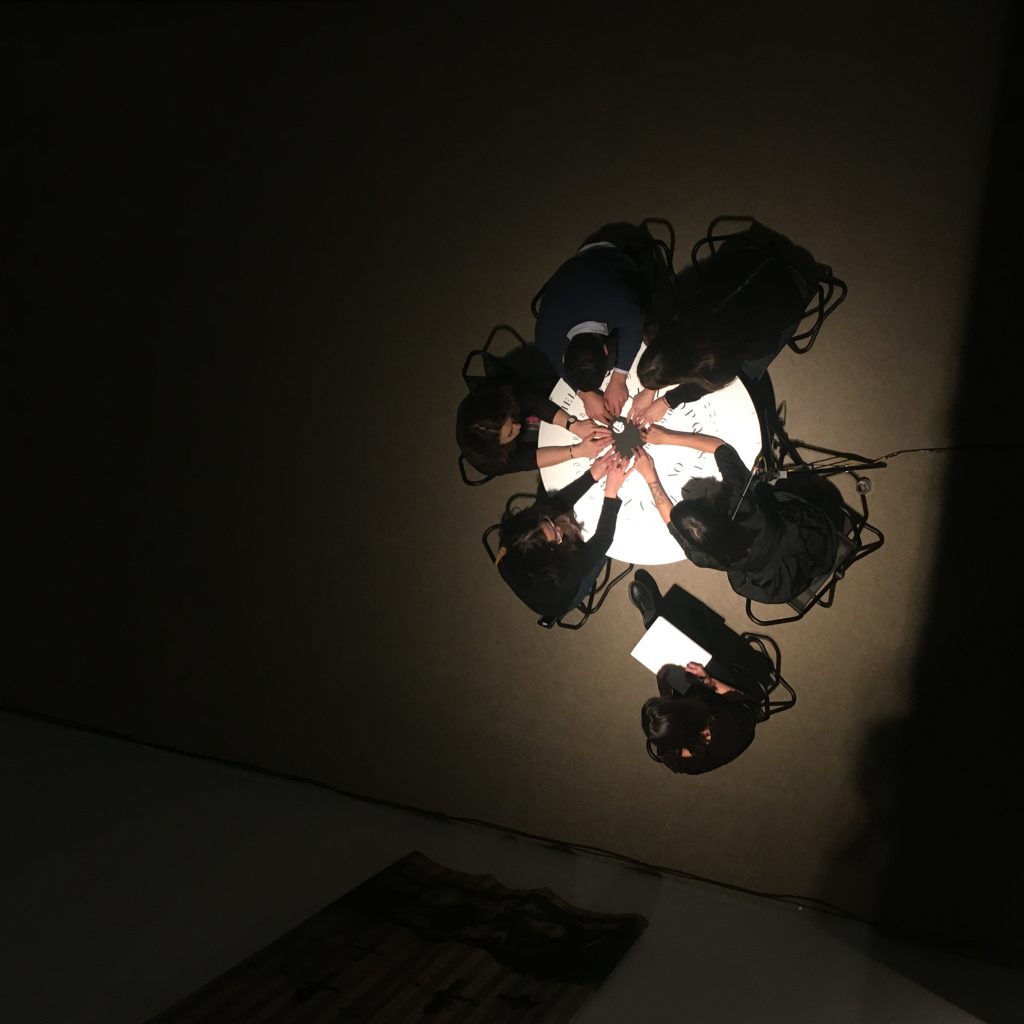

Hagar Ophir, ‘Recalling History; Sitting I; Conjuring a Looted Wooden Box’, Performance. As part of Errata (curated by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay). Antoni Tàpies Foundation, Barcelona, 11 October 2019–12 January, 2020, Tapies Foundation, December 12, 2019. Image copyright: Natasha Christia.

I will never forget my visit, last December, to Errata, an exhibition curated by Ariella Azoulay, at the Antoni Tàpies Foundation in Barcelona. I was in the audience of Hagar Ophir’s Recalling History,20 a spiritualist encounter which created an experimental space for producing a nonlinear account of history. Revolving around a recovered wooden box from Palestine, the performance ‘employed séance practices in order to communicate with both the dead owners of the looted object and its looters’.21 Transcending rationality, belief, or disbelief, the event culminated in a powerful two-hour immersive encounter of voices and subjectivities around a table. Narrating a new story, it encouraged a form of collective healing for both the Palestinian and Israeli community members that were present, as well as for us, the rest of the assistants.

Healing is not always the goal, and “art has a different goal than social engineering”.22 But engineering understood as the embodiment of a political experience—from the standpoint of acknowledging what the feelings of the community are and what they hold on to—can be energised through situations revolving around a book. “Gain[ing] an understanding of our contemporary culture as already dead and musealised […] comes not so much from putting on the mask of past cultures, but rather from seeing the face of contemporary culture as a mask and comparing it to other masks”, argues Groys.23 This entails, to begin with, performative operations, such as enacting, trying, failing, and acting again.

I find myself rewriting and rewriting the lines of this essay, word for word, reading aloud, fighting with the meaning that advances only with reluctance. My writing brings me full circle to the first lines of this essay, and to the lexicon of situations I have attempted to provide.

To fully grasp its spirit, one should see perhaps the poetics of writing, as well as the resistance it involves. In her performance Omaggio al romanzo delle stragi di Pier Paolo Pasolini, at the Academia Belgica in Rome, the artist Chantal Vey, pencil in hand, wrote out word for word a Pasolini column published, in 1974, in Corriere della Sera. Overwriting what she had written over the course of two hours, she describes the result thusly: “His strong, powerful words are traced on a single line or a few, either in graphite pencil or in black or dark red ink. Gestures and jerky reading set the rhythm and guide the handwriting, applying more or less pressure, allowing the various graphic forms to thus compose spontaneously. The lines overlap, the words, one after the other, cover each other, hiding the meaning to become woven lines, stripes of imprints”.24

The toolbox is not, as Agamben put it, “passed blindly to the act”. It is not a prescription, it is not a dictate. It is not exclusively associated with the condition of editing and reading. Rather, it embraces the imagination, an intense dialectical predisposition, strategies of disbelief, and the ruthless thriving and sharing of the (photo)book with(in) other situationist apparatuses, such as the exhibition and the theatre. And its only condition, which resonates and reverberates in many directions, is that of potentiality. To do and not to do so.

Chantal Vey, Omaggio al romanzo delle stragi di Pier Paolo Pasolini [Homage to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘The Novel of the Massacres’], writing performance and exhibition, Academia Belgica, Rome, April 25, 2019. Image copyright: Chantal Vey. Image © Anh Thy Nguyen.

Natasha Christia is an unaffiliated curator, writer and educator based in Barcelona. She is also a collection consultant and a dealer specialised in fine art photography and photobooks.

___

1 “If all creation were a potentiality to do something, a potentiality which can only be passed blindly to the act, then art would be reduced to the execution of an order or even a prescription which has dismissed and denied the resistance of the act, the potentiality of not to do so”. Giorgio Agamben, ‘Resistance in Art’, lecture, The European Graduate School (August 2014), youtube.com/watch?v=one7mE-8y9c [all URLs accessed 31 July, 2020].

2 Boris Groys, ‘The Museum as a Cradle of Revolution’, e-flux 106 (February 2020), e-flux.com/journal/106/314487/the-museum-as-a-cradle-of-revolution.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Uncensored Books is an ongoing (photo)book-based exhibition. Books, in addition to for their form, narrative, and conceptual framework of production and dissemination, are employed here to address the topic rather than to venerate the book form. They become the starting points of a generic narrative that unfolds on the wall in the form of ephemeral/DIY installations preserving their guerrilla nature. Exhibitions: Medphoto Festival, Rethymno (Crete), September 2017; Minimum Studio, Palermo, June–July 2017; On-site Greenhouse installation, with Minimum, during the Una marina di libri festival, Palermo, June 2017; Uncensored Books Ozone Gallery, Belgrade Photo Month, April 2017. For more information, see, natashachristia.com/curating/uncensored-books-2017.

6 Reversiones: Reversioned Books by Lewis Bush, Vincent Delbrouck, Brad Feuerhelm and Melinda Gibson, E.Folio.001, Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City, 23 November, 2017–1 April, 2018, natashachristia.com/curating/reversiones-2017.

7 Bernadette Buckley, ‘The Politics of Photobooks: From Brecht’s War Primer (1955) to Broomberg & Chanarin’s War Primer 2 (2011)’, Department of Politics and International Relations, Goldsmiths, University of London (April 2018), http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/05e7/d32c5c4801cba8bd1e010b061fa6af089eb5.pdf?_ga=2.23433145.2064225915.1595854740-1241457478.1595665973

8 “My aim is not to make a better book or a perfect product for the market but to be free to travel through memories, archival material stored inside my boxes, and my DIY process. It is a fast creative process, with failures and flashes of beauty. It is anti-poetry”. Quoted from an oral interview of the artist by the author, October 2017.

9 ‘Deconstructing the (Photo)book and Reinventing it in Space’, Zoetrope, Athens, 21–22 December, 2019, zoetropeathens.net/events-news. Workshop led by the author. Participants: Dimitris Mytas, Spiros Paloukis, Alexandra Saliba, Stratis Vogiatzis, Yorgos Yatromanolakis.

10 “Radical intimacies are dialectic, embedded in everyday life and counter to systems of oppression, especially neoliberal capitalism. They are communicative and refer to a social practice in the sense that they seek impact beyond the production of visual artefacts. They manifest themselves in the process of production, distribution and reception, but understanding that they go beyond representation is crucial. They are ontological in the sense that they acknowledge design as a general human activity. They are interpersonal, although they can also be mediated. Radical intimacies truly unfold as a practice and methodology when photography and design include friendship, dialogue, pleasure and collaboration as a part of their creative process of making. Radical intimacies build alternative worlds, they create autonomous spaces and occupy places meant for other kinds of relations”. Oliver Vodeb, ‘Radical Intimacies: (Re)Designing the Impact of Documentary Photography’, Trigger #01: Impact (Amsterdam: Fw:Books/FOMO).

11 Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London and New York: Verso, 2019).

12 The ideas underpinning Ariella Azoulay’s work on distinguishing the event of photography from the photographic image were first articulated in her books The Civil Contract of Photography (Zone, 2008) and Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (Verso, 2012). The extracts included in this text are quoted from ‘On Photography and Potential History’, lecture, Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (25 October, 2012), youtube.com/watch?v=xnJaJK4oAmI.

13 ‘Potential History: Photographic Documents from Mandatory Palestine’, curated by Ariella Azoulay, guided tour pamphlet. Remco de Blaaij and Anna Colin, 10×10: Nineteen-forty-eight, European Cultural Congress, Wrocław, 8–11 September, 2011.

14 Susan Meiselas, Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (New York: Random House, 1997). Also see, akakurdistan.com.

15 Ibid.

16 James Pfaff, Alex & Me (Ravenna: Danilo Montanari, 2016).

17 For more information on each iteration of Alex & Me, see, jamespfaff.com.

18 Kader Attia, The Field of Emotion, artist’s website (2018), kaderattia.de/the-field-of-emotion.

19 Errata, Antoni Tàpies Foundation. Curated by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay & Carles Guerra. Barcelona, 11 October 2019–12 January, 2020, fundaciotapies.org/en/exposicio/ariella-aisha-azoulay-errata.

20 “Imagine a table in a dark room; a theatre, or a secret prayer room. Sitting together around the table are experts who come to recreate a non-historical story of a past. They are rewriting and releasing to it through their body and shared thoughts. The historian—the medium, is in a duet with her subject of research: the dead guest or the ghost that is being called from the occult to the room. The medium conjures the entities to speak and become materialised through the questions and presence in the participants of the séance, and the believing mind and bodies of the audience standing around”. Hagar Ophir, ‘Recalling History; Sitting I; Conjuring a Looted Wooden Box’, Selection of Works (2020), PDF, hagarophir.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/selected_works_2020.pdf.

21 Ibid.

22 Boris Groys, op. cit.

23 Ibid.

24 Chantal Vey, Omaggio al romanzo delle stragi di Pier Paolo Pasolini [Homage to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘The Novel of the Massacres’], writing performance and exhibition, Academia Belgica, Rome, 2019, chantalvey.be/projects/%e2%80%a2writing-performance.