Stefan Vanthuyne

For Brigitte / © Titus Simoens

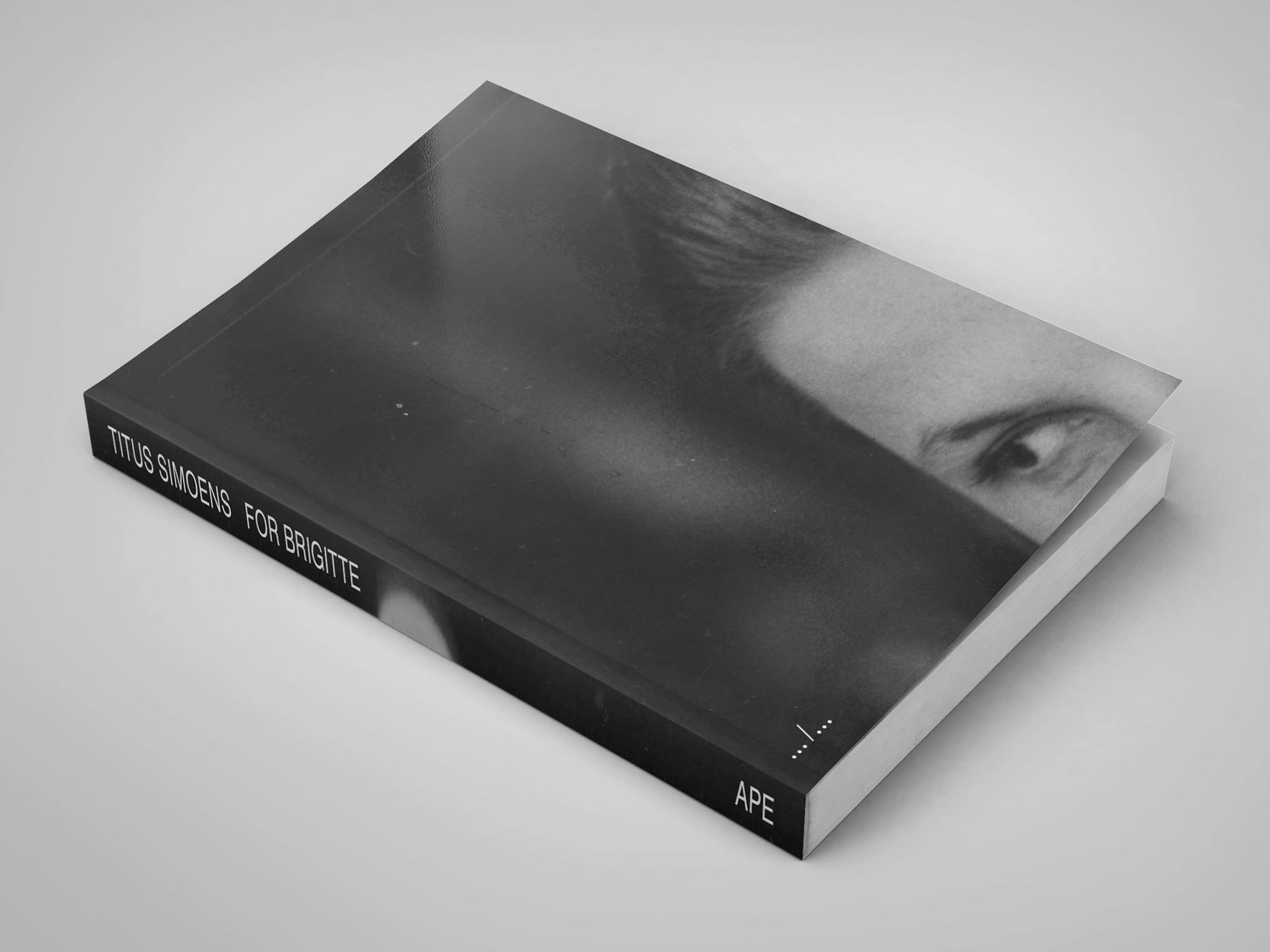

Working closely together with her sister Lieve, who wanted to surprise Brigitte for her seventieth birthday, photographer Titus Simoens created a book out of old photographs. Leaving the design partly up to chance, Simoens builds a narrative that is at once accidental and original.

It started with a letter shared on Facebook. One of the lecturers at KASK Ghent had received a mail with an unusual request from a woman called Lieve, and had posted it in the Facebook group of the school’s photography department.

‘I have a wish concerning my sister (who was recently struck with cancer), wanted to surprise her with some old photographs and clippings of her college years.’

“I remember waking up, checking Facebook, reading the post and thinking: yes, that’s my next project”, Titus Simoens recalls. The young photographer, who received his BA in 2008, had reenrolled at KASK Ghent to obtain his MA and had just about finished Tu me dis. More an artist’s book than a monograph, Tu me dis was a first sign of his departure from the more traditional documentary photography he had been doing up to then.

From 2011 Simoens worked on a project on school pupils under a strict regime, a project taking him to a naval college in Belgium, a kung fu school in China and a boxing school in Cuba. Here Simoens already wasn’t simply an observer. He gave the boys disposable cameras, allowing them to come up with a different image, a snapshot image, of their lives. In 2015 the trilogy became a monograph: Blue, See Mount Song Los Domadores.

But Tu me dis – You tell me – was something very different. This was about the relationship between photographer and subject; this was about the power a photographer had. And it was personal: at the very end of the book the subject, a young woman he met in Arles, responds with a poignant letter. “Tu me dis was about a real encounter with a woman”, Simoens says. “About jumping into her life for a just brief moment, but with an intense involvement.”

To Simoens, the letter shared on Facebook felt like it could be something similar. “I picked up the phone and called Lieve. It turned out that I was the second photographer to call her. The first one, however, had suggested that she might be better off with a graphic designer, but she insisted that she preferred to work with a photographer. So I told her I was very curious about their story, about why she wanted to do this for her sister.”

For Brigitte / © Titus Simoens

Simoens visited Lieve at her house. “You could tell that she was indeed going blind”, he remembers. “She still has one good eye, but she mostly looks for you by following your voice. She showed me pictures of her family and of her twenty-year older sister Brigitte. Brigitte was the pretty sister, the beautiful sister. Every boy in the village was crazy for her. She was the naughtiest one of the family also. She had lived the most adventures, had moved to the United States for a couple of years… To me she sounded like an amazing woman.”

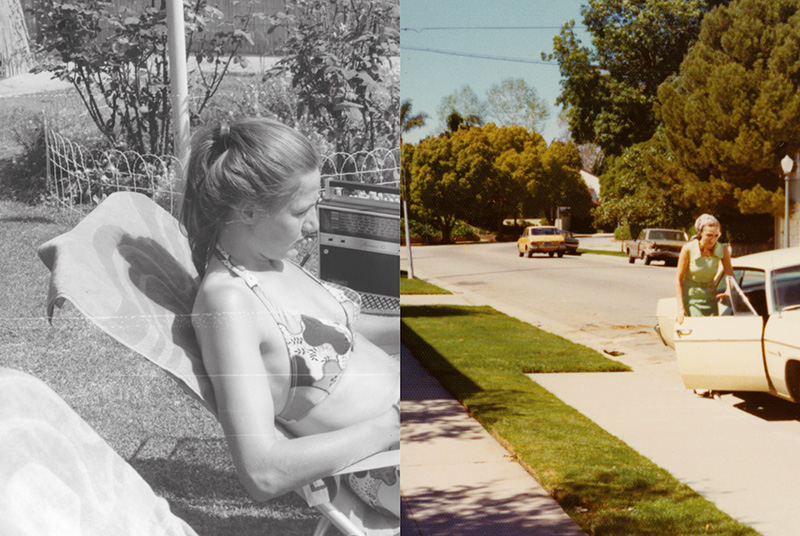

Lieve kept showing him photographs of Brigitte. But Simoens asked if he could see more, so she gave him the photo albums Brigitte had – her children made sure he got them. “I took all of those pictures and family albums home with me. I started selecting images, intuitively going for those where she glowed, forming my own image of Brigitte based on the information Lieve gave me, but also from a male perspective, simply choosing pictures where I thought she looked sexy.”

Simoens ended up with around 120 images. All the while, for a period of five weeks, he kept visiting Lieve, every Tuesday. He photographed her, wanting to get to know her as well, since she was a key player in this story. “It was her intention to create this book as a gift for Brigitte. It was she who told me all about Brigitte, so to me she was a very interesting person. But at the same time I was working with Brigitte, who I had never met. I briefly considered doing a project about Lieve as well, but I didn’t follow through on that.”

Simoens scanned all the images he selected. Some photographs were small so he scanned them small, others he scanned bigger. He started to think about a book format, so he made a grid in Indesign. He knew he wanted two images per spread, one on the left and one on the right, and on each page the photograph printed full bleed.

“So there it was on my screen, a book full of empty pages. And there they were, 120 scanned photographs. Having no clear idea on where to start, I decided to just load them all in at once, in the order I had scanned them – which is not in chronological order – and just see what happens. The whole process was very subconscious.”

Indesign creates its own crop of every photograph. Based on the resolution of the digital file, only a certain percentage of the full scale image is presented on the book page. Because of this random crop, Simoens started to look at the photographs in a completely different way. “Before I was so focused on Brigitte, but now I was noticing different elements. Like a man in the background. Bricks in the wall that draw your attention. Flowers… All of these unexpected little details somehow defined her environment and became more important in the photographs. It gave me the feeling like I was much more involved in Brigitte’s life. Like I was much closer to her.”

For Brigitte / © Titus Simoens

The meaning of a snapshot, Catherine Zuromskis writes in Snapshot Photography, is a deeply personal one. According to the American scholar the snapshot “might be classified as the precious photographic trace of a cherished person, moment or thing.”1 As a consequence, the snapshot generally only circulates within a small and intimate circle. “Each snapshot addresses a specific, private audience of personal relations and friends for whom the content of the image is particularly relevant and meaningful.”2

The creative potential of the individual reading of the family album, then, Zuromskis argues, is necessarily limited by the scope of the familial network. Not everyone is allowed to interpret the family history, because not everyone is allowed acces to the family album. “In both the individuals it represents and those for whom it represents, the album is constructed as a private text addressed to a private collective of participants who may contribute to its narrative meanings.”3

Here Simoens, who is an outsider to the familial network, is allowed access to the family album by one of the family members, albeit with a predetermined purpose. He is allowed to interpret it, albeit directed by the information given to him by Lieve, who from the start has conceived this project as an endearing ode to her sister. But while his specific image selection quite easily meets these expectations of representation, it is Simoens’s accidental sequence and design that surprises.

Though Brigitte is in fact in every picture in the book, we don’t always see her, nor do we always get a clear idea of the context in which the photograph was made. We also notice certain absences – people you sense are there, but have now been randomly cut out of the frame, people we probably wouldn’t even have noticed if they were present. This interference not only sidesteps snapshot conventions, it also creates space for a less private, less predictable, more open and more engaged reading.

When speaking of photobook narratives, writer Gerry Badger often uses the analogy of music, comparing a photobook sequence to a musical composition. Referring to the work’s meaning, instead of the specific storyline in the conventionally understood sense, Badger also states that most photographic sequences are in fact more abstract in actuality than they might appear.4

Looking at how the narrative came about in For Brigitte, John Cage’s indeterminacy in music, where some element of a composition is left to chance, comes to mind. More specifically his Music for Piano, a series of 85 indeterminate musical compositions for piano. In some of these works, notes were determined by the imperfections on a piece of paper – imperfections you could see while holding it to the light. “Suddenly I saw that the music, all the music, was already there”, Cage said.5

For Brigitte / © Titus Simoens

Only two physical copies of For Brigitte were printed. One for Brigitte and one for Simoens. About a month later, after showing it to a few people and getting good reactions, Simoens started to think about it as an autonomous artistic project. So he asked Brigitte how she felt about the idea of bringing the book to a wider audience. She thought about it, and pretty soon gave him permission to do so. Pretty soon Art Paper Editions, who had already published Tu me dis, decided to get behind this project as well.

Working with found or archive material, or with family albums is nothing new. Usually, the owner or the maker of the images, or the protagonists in the photographs, are out of the picture – having passed away or disappeared. Mariken Wessels is one artist known for working with personal archives and making books based solely on what the images, objects and letters, and sometimes additional information from friends or acquaintances, tell her. Though it is based on true events – she called her latest book Taking Off. Henry my Neighbor (2015) ‘a true picture story’ – Wessels clearly is the author of the narrative. The story laid out in the pages is how she artistically reconstructed it.

Things are a little bit different, a little more delicate also, when you’re making a book commissioned by one sister, about the other sister who is going to receive it as a birthday gift, both of them very much alive and present. How far can you push your own artistic agenda? At what point can you claim the images in the book as your own – if at all? How do you deal with authorship then? In The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji (2016), where he does beautiful things with the archive of Masanao Abe, artist Helmut Völter writes that one must revisit the question about how to strike a balance between different interests, such as the historical, the aesthetic and the poetic.6

“I was very much aware of the fact that I was working with someone else’s images”, Simoens says. “And during the whole process of editing, they always remained their images. At that time, I was learning a lot about authorship at school, discussing the work of Richard Prince. So I became fascinated by the question of when you could claim something as your own. Is it when you take an existing image and you simply put in a different context? Is it still the same image then? I tend to think it isn’t.”

When Lieve asked him if he could give her the scans he made from the original photographs – she wanted to use them for invitations – he told her she could. But not the cropped versions used in the book. “You see, I had already considered those as my own images, because of the intervention I did. Lieve immediately understood. The original scans were obviously also theirs, since her family made the original photographs.”

“I became fascinated by the question of when you could claim something as your own. Is it when you take an existence image and you simply put in a different context? Is it still the same image then? I tend to think it isn’t” (Titus Simoens)

“I kept them involved in every step of the process of turning it into an artists’ book. For instance, I wanted to use the original mail Lieve had sent to the KASK, so I asked her permission to do so. “Don’t you think it’s too much of a weird scribbling?” she asked me. Even there she was a little bit hesitant. I get that. All of sudden what was just a moving, intimate gift between two sisters becomes something public. A part of their lives is now in the open. But therein also lies the beauty of this project.”

Taking all things into account, the narrative of For Brigitte is an odd one. Of course, there is a light and playful aspect to it. At the same time, being rooted within the family album, it is an intriguing experiment, in which the ideas behind authorship, sequencing and book design become important. The way chance was used, is like a subconscious recognition of the very personal and private character of the photographs. Here Simoens takes a step back as the author, by refraining from pushing an artistic agenda and by leaving room for interpretation. In a way, one could say this is where Simoens and Brigitte meet.

The result is a story at once original and coincidental, free in its flow. Bumping into unforeseen and fortuitous juxtapositions, pregnant with meaning, one cannot help but wonder what might lie behind a woman’s snapshot smile.

“It was the way the first image on the cover, a wedding picture, had turned out that made me decide not to change anything to the book”, Simoens says. “The way her eye fell into that lower right corner. All of a sudden there was this tension throughout the book, a tension I would have never been able to deliberately seek out.”

“If I had taken on a more active part in the editing and the page layout, there would have a been a lot more doubt. I would have questioned every decision, every action in terms of creating the narrative. Can I do this? Is it allowed or is it correct? Leaving it up to chance means that I didn’t actually write the narrative, but I did create a new space for it to occur and unroll; I saw it happen and I gently guided it.”

“I didn’t create the story,” Simoens concludes, suddenly sounding very much like Cage. “The story was already there.”

For Brigitte / © Titus Simoens

__

1. Zuromskis, Catherine. Snapshot Photography. The Lives of Images, The MIT Press, 2013.

2. Zuromskis, pp. 48.

3. Zuromskis, pp. 57.

4. Badger, Gerry. “It’s All Fiction. Narrative and the Photobook.” Imprint. Visual Narratives in Books and Beyond, ed. Hans Hedberg, Tyrone Martinsson, Gunilla Knape, Louise Wolthers, Art and Theory Publishing, 2013, pp. 15-47.

5. Johnson, Steven. The New York Schools of Music and Visual Arts, Routledge, 2002.

6. Völter, Helmut. The Movement of Clouds around Mount Fuji, Spector Books, 2016.

Content for this platform is written by non-native English speakers. If you find some flagrant mistakes, please don’t hesitate to let us know.